Text messages are gold. They are typically sent without the forethought of a letter or email, so they typically reveal persuasive evidence of the sender’s mental state at the time the message is sent. Relevant texts between the parties are coming in. But texts to a third party present special issues of authentication. This article discusses those issues.

A text message is a writing that must be authenticated. (Evid. Code §§ 250, 1401(a).) Authentication requires a showing that the writing was made or signed by its purported maker. It’s important to remember that the maker’s testimony is not necessary. (Evid. Code § 1411.) Instead, authenticity may be established by the contents of the writing (Evid. Code § 1421) or by witness testimony, circumstantial evidence, content, or location. (People v. Goldsmith (2014) 59 Cal. 4th 258, 268.) The recent published case of Adoption of X.D. (2025) WL 2753550 addresses self-authenticating writings.

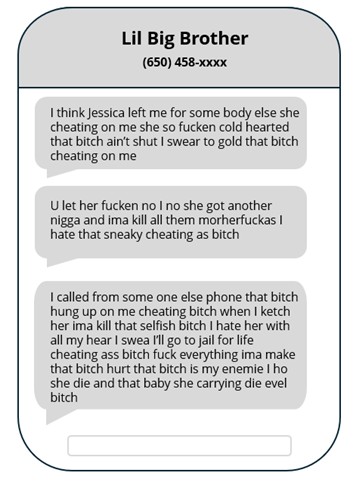

In Adoption of X.D., a single mother put her child up for adoption on the day he was born. When the biological father found out, he opposed the adoption. The issue at trial was whether the father could demonstrate his full commitment financially, emotionally, and otherwise to his parental responsibilities to the child. The mother disputed this. To support her argument, she presented text messages from the father that said, inter alia, “Ima make that bitch hurt that bitch is my enimie I ho she die and that baby she carrying die evel bitch.” (Misspellings original.) Not exactly the image of a loving father, so his attorney moved to exclude the text messages. The father caught a break when the trial court excluded the text messages and nullified the adoption.

The trial court excluded the text messages because they weren’t sent from the father to the mother. They were sent to a third party—the father’s sister—who took a screenshot and forwarded the screenshot to the mother. The mother tried introducing the screenshot as evidence of the father’s lack of emotional commitment to the child. The trial court excluded the screenshot because the sister did not testify and authenticate the messages. Without the text messages in evidence, the trial court ruled for the father and restored his parental rights.

The mother and adoptive parents appealed. The appellate court faulted the trial court for ignoring Evidence Code § 1411, which says that the testimony of the subscribing witness is not necessary to authenticate a writing. The justices took a closer look at the screenshots, which showed the sender’s name, the sender’s phone number, and the content of the text messages.

The appellate court found an abuse of discretion because the screenshot was self-authenticating under Evidence Code § 1421. At trial, the father admitted that his phone number matched the number of the sender; he admitted that his sister called him “Little Big Brother” (which matched the name of the sender); and he admitted that he accused the mother of cheating on him (which matched the content of the texts). Those combined facts were circumstantial evidence that the father sent the text messages, so the mother had carried her burden of authenticating them. (Citing People v. Goldsmith (2014) 59 Cal. 4th 258, 268.) The fact that conflicting inferences could be drawn regarding authenticity goes to the weight—not admissibility—of the writing. The appellate court reversed the trial court with directions that the adoption should proceed.

The appellate court found an abuse of discretion because the screenshot was self-authenticating under Evidence Code § 1421. At trial, the father admitted that his phone number matched the number of the sender; he admitted that his sister called him “Little Big Brother” (which matched the name of the sender); and he admitted that he accused the mother of cheating on him (which matched the content of the texts). Those combined facts were circumstantial evidence that the father sent the text messages, so the mother had carried her burden of authenticating them. (Citing People v. Goldsmith (2014) 59 Cal. 4th 258, 268.) The fact that conflicting inferences could be drawn regarding authenticity goes to the weight—not admissibility—of the writing. The appellate court reversed the trial court with directions that the adoption should proceed.

The justice system reached the correct result in this case, but it caused a delay of nearly a year while the parties waited for the appellate court to overturn the trial court’s ruling. This could have been avoided with a simple citation to the Evidence Code’s rules for authentication (section 1400 et seq.) and Goldsmith.

- Partner

Donald J. Magilligan is a partner at Cotchett, Pitre & McCarthy based in the firm’s San Francisco Bay Area office. Magilligan specializes in complex litigation involving wildfires, wrongful death, and business fraud.